Moving forward, the City will actively encourage organizations like community nonprofits or medical organizations to operate and fund one or more CUES.

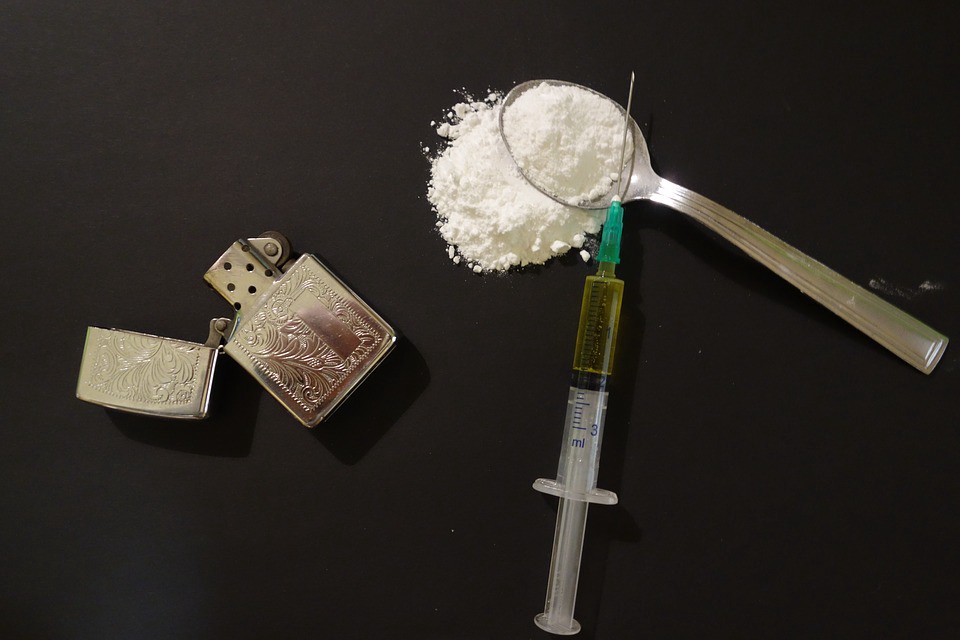

This past Wednesday, the city of Philadelphia announced plans to encourage organizations to develop Comprehensive User Engagement Sites, in which opiate addicts would be provided a safe space within the city to use heroin and other opiates under medical supervision.

“These locations are similar to safe injection sites,” a press release from the city says, “but they also would offer a wide range of other important services to meaningfully assist those struggling with addiction.”

The other services, which would be provided in a walk-in setting, would include referrals to treatment and social services, wound care, medically supervised drug consumption and access to sterile injection equipment and Naloxone.

If such sites were opened in the city, Philadelphia would become the first city in America to embrace safe injection sites, and the third in North America. Vancouver was the first North American cities to embrace the idea, where it has been met with success, according to Vancouver officials. The use of safe injection sites has been utilized considerably more in various European countries, including the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Germany and Switzerland. Toronto opened the second North American safe injection site last year.

The theory behind CUES is they will reduce public drug use, prevent overdoses, prevent diseases by providing users with clean needles, provide better access to treatment — and most importantly — save lives. In the event of an overdose, medical professionals will be nearby to administer Narcan, a drug that blocks the effects of opioids and can reverse an overdose.

There is one key difference, however, between what Philadelphia is proposing and what other countries have done, and that’s supplying the actual heroin.

Research shows the best way of treating heroin addicts is to supply them with methadone or suboxone, both of which are opiates that eliminate cravings and withdrawal systems for heroin addicts. However, according to the federal government’s National Institute on Drug Abuse, methadone and suboxone are ineffective treatments for up to 40 percent of users. For this group of people, research says, the most effective treatment is medical-grade heroin.

“[Supervised injectable heroin] is found to be an effective way of treating heroin dependence refractory to standard treatment,” reads the conclusion in a 2017 study in the British Journal of Psychiatry. “The prescribing of diamorphine (pharmaceutical heroin) as part of treatment for heroin addiction initially appears counter-intuitive. Addiction is increasingly recognised as a chronic relapsing disorder for which effective treatments exist. However, public responses to addiction tend to polarise around addiction as ‘badness’ or addiction as ‘illness,’ and counter-intuitive treatments often generate strongly felt passions associated with these differing frames of reference. When debate gets heated, it is particularly important for science to contribute cool-headed analysis.”

In the 14 years since Vancouver’s safe injection site opened, injection drug use, overdose deaths and the HIV infection rate have all declined, Patricia Daly, chief medical health officer for Vancouver Coastal Health, told Vancouver-based newsradio station News 1130. VCH is the public authority that oversees and funds the Vancouver safe injection site. Perhaps even more impressively, the city’s life expectancy has shot up a whopping 10 years, she said.

For many in the community, however, the obvious question is, “Where are we going to put the sites?” During the district attorney race, many residents were adamant they would not welcome such sites in their neighborhood.

“Those [opiate users] are already in their neighborhood,” said Jillian Bauer-Reese, a professor at Temple University who teaches a class called Solutions Journalism: Covering Addiction. “This should be a place where people could go and, under medical supervision, use a substance and get treatment when they’re ready for it. This whole NIMBY thing — Not In My Backyard — has got to stop.”

“I think they’re necessary,” said Elvis Rosado, the education and outreach coordinator for Prevention Point, a Kensington-based private nonprofit that provides harm-reduction services to Philadelphia and the surrounding area. Rosado said that often users will go to an assessment center seeking help, say on a Tuesday, but a spot might not be available for them until Saturday.

“[So] for Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and part of Saturday, that person was still using,” he said. “Still at risk of overdose, still at risk of infections, still at risk of HIV or anything else, still at risk of arrest of getting incarcerated because of where they are using and other things that may or may not be happening.”

“I can 100 percent say that I would have no problem — as a person with a 6-month old — having a safe injection site next to my house,” said Bauer-Reese “The stigma has got to go.”

Moving forward, the City will actively encourage organizations like community nonprofits or medical organizations to operate and fund one or more CUES.

While the City will not operate CUES, agencies and officials will bring together key stakeholders and identify organizations that are interested in operating, funding or offering a location for such a facility.

“Philadelphia’s fatal overdose rate is the worst in the nation among large cities, and incidents of overdose have steadily increased to an alarming degree,” said Mayor Jim Kenney about the decision. “I applaud the work of the Task Force and city leadership in taking this bold action to help save lives.”

CUES are the latest part of a much broader strategy to address this public health crisis. The Mayor’s Task Force to Combat the Opioid Epidemic is informing the City’s efforts to reduce opioid abuse, dependence and overdose in Philadelphia.