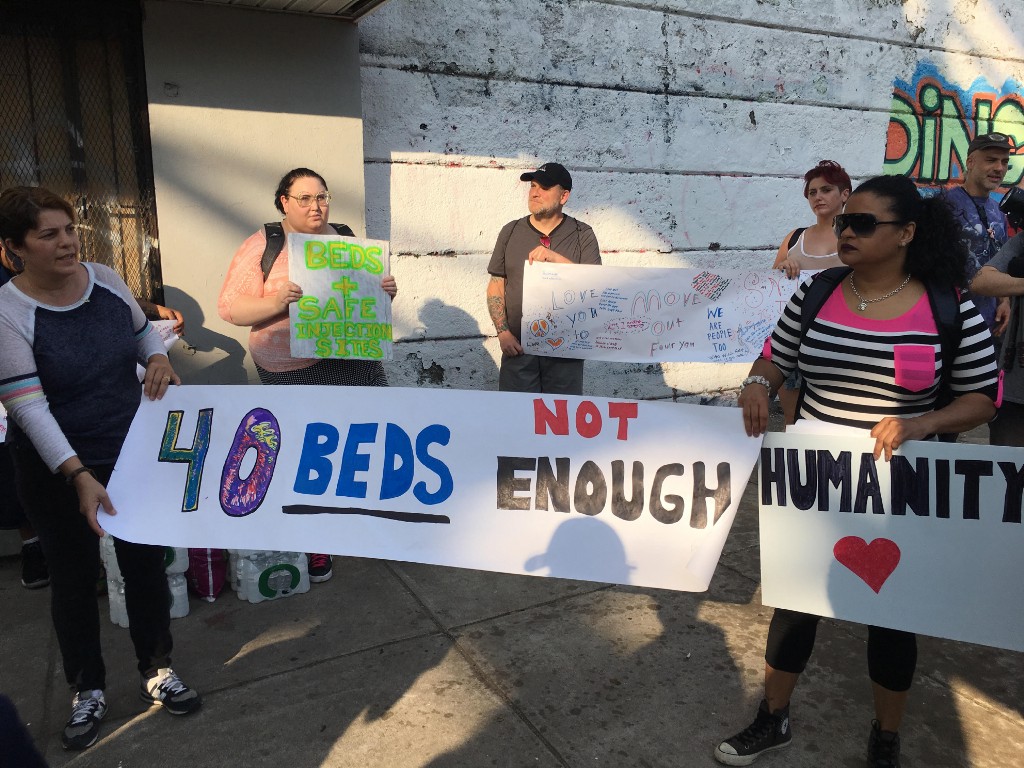

Protesters and came out to the homeless encampment at the corner of Kensington and Lehigh Avenues to speak out against the city’s decision to evict all of the homeless people from underneath the Conrail bridge.

Protesters came out to the homeless encampment at the corner of Kensington and Lehigh avenues to speak out against the city’s decision to evict all of the homeless people from underneath the Conrail bridge.

“They have nowhere to go,” said protester Britt James Carpenter, who lives in the neighborhood. “Plan A, they took them off the tracks. Plan B — there was none. So this is what happened. And a year later, this is what’s happening. They’re suffering again. They were thrown out of their first home and now they’re thrown out of their next home.”

“Everybody needs a little help here and there,” said protester Tim Timsdale, who said he had previously been homeless in the neighborhood after his house caught on fire. “Nobody should be treated wrong. Try to help them find a place to go, you know what I mean?”

Carpenter conceded that living under a bridge is no way for any human being to live.

“But,” he said, “they also don’t [deserve] to be thrown out again. They were already thrown off the tracks, which was their home for many years, where they weren’t causing problems.”

Many protesters complained the city didn’t have a plan in place for after the homeless encampments were cleared out. They said the city didn’t have enough places to put these homeless people and didn’t have enough resources to take care of them.

“I don’t think they should be evicted,” said protester Harmony Rodriguez, who came as a member of a socialist group called the Workers’ World Party, “because the city isn’t providing enough space for everyone and it’s not providing enough resources — not good enough resources. It’s not providing good enough treatment. So while they’re here, they’re safe and they have each other.”

Councilman Mark Squilla, who was present at the protest, pushed back on that claim a bit. He said there were 40 beds available at Prevention Point, 40 beds available at a new recently opened shelter on Kensington Avenue, and an additional 40 beds at a separate North Philly shelter. Squilla told the Star that in addition to these 120 beds, he’s working to try to open another 80 beds by the end of the summer. However, Squilla said, “it’s not official yet.”

Additionally, Squilla said more than 100 people have gone into either low-barrier housing or to rehab since the pilot started.

“So to me,” he said, “so far, the pilot has been successful. We haven’t reached the end of it yet at this point, but now we’re looking at how this encampment had started. How we can help the folks that are here, but also help the people in the surrounding community.”

He also pushed back against people who feel the homeless people shouldn’t be evicted.

“As a city, we cannot say that it’s OK to have folks live in these types of conditions,” he said. “We’ve got to try to help them the best we can. We’ve [come up] with additional money from this year on the budget to do that and we even asked for additional dollars for low-barrier housing and respites.”

He also pushed back against people who said the clearing out of the encampment underneath the tunnel was just like when they cleared out Gurney Street by the Conrail train tracks. Wouldn’t people just find another spot out in the open to congregate and inject drugs? No, Squilla said, “this is a whole different program.”

At Gurney Street, “they had no people trying to get them into respite centers or into drug treatment,” Squilla said. “They just cleaned it up. This is a whole different process. I think we learned from that, and, as a city, we support this outreach to try to get folks into treatment, which they need. If we can get 50 people into treatment and they go on to be successful and sober or at least stable, then I think we did a great job. We got them off living in the street and got them a chance to renew their lives.”

About a block away from the protest on the other side of the bridge, a group of counter-protesters congregated at the corner of Kensington Avenue and Tusculum Street. Among them was Patty-Pat Kozlowski, Republican candidate for Pennsylvania’s 177th state representative district.

“I feel like we’re in an episode of the ‘Twilight Zone,’” she said. “That we actually have to protest protesters who don’t want the city to clean up the Kensington, Port Richmond and Fishtown neighborhoods.”

She said no one among the counter-protesters wants to see anybody in the tunnel “die or get harmed or thrown in jail.” However, she said the media and city officials focus too much on what life is like living in the tunnels, and not enough on the quality of life for all the law-abiding Kensington residents who aren’t living under the tunnel.

“It’s horrible what’s happening down underneath these tunnels,” she added, “but it’s seeping into our neighborhoods. People in this corner, we feel like we’re sitting in an emergency room with a cut finger compared to their problems that they have, but our quality of life — everyone has either gotten robbed or had their patio furniture taken off their porch, their air conditioners taken out of their window, their cars broken into. You talk to any guy who is a laborer in Port Richmond or Fishtown or Bridesburg and either their work van has gotten broken into or tried to get broken into so that the junkies can take their tools and sell them for their next high. It’s a horrible quality of life.”

Kozlowski said her solution to the problem involves “mandatory treatment.”

“And if they don’t want to go,” she said, “I think then we have to 302 them and say that they are not sane. What sane person lives a life like this? Underneath a tunnel, sleeping in a tent or a filthy mattress?”

In Pennsylvania, to “302” somebody means to admit someone into a psychiatric unit involuntarily.

What does Kozlowski think of experts who say that you can’t force people into treatment?

“Where are the experts for the people whose neighborhoods are being killed by this?” she asked. “How come we don’t have any experts to fight for us? That’s why I’m here today. To tell you the truth, I care about people in Fishtown and Port Richmond and Bridesburg and Kensington and Harrowgate. I care more about them than the people under the tunnel.”

Many other residents in the counter protest voiced their opinions as well.

“These people need help. I understand that,” said Port Richmond resident Christine Sperber. “There’s got to be an answer, and the city has it. They have the money, they have all these empty places, abandoned places they don’t take care of. There’s empty homes — find somewhere to put them.”

Sperber said she would be in favor of safe-injection sites.

“If there’s somewhere safe for them to go, then give them the needles and stuff that’s fine,” she said. “That way they’re not all over the street. Until they’re ready. I know that they’re not going to help themselves until they’re ready. You can push them in there and if they’re not ready, they’ll come out and do it all over again. They either hit rock bottom or they die.”

“I live right here with my kids and everything and it’s just overabundant,” said Fishtown resident Natalie Thomas, who lives less than a block away from the bridge. “They’re comfortable, they all get the help, they all have the opportunity to get the help, but they don’t want it.”

Many people who are addicted to opiates and are living or have lived in the Kensington encampment have disputed this, however.

“I tried to get help for months and been kicked out of facility and facility,” said Ryan Deeny, who said he was eight weeks clean to the day on the night of the protest. “CBH says they want to help, but if they don’t have funding, you’ve got to go.”

Deeny is referring to Community Behavioral Health, a not-for-profit corporation contracted by the City of Philadelphia to provide mental health and substance abuse services for Philadelphia County Medicaid recipients.

Deeny said he’s had trouble getting into many hospitals in the area, including Episcopal, Friends and Mercy.

“It takes six, seven days to get into treatment and you have like one hour for an addict to say yes, and that’s it,” he said. “It might be too long.”

Charles Eason, who had lived in the encampment until he was placed in the new Kensington Avenue shelter, said he hasn’t had any luck being admitted into a rehabilitation facility.

“I’m trying to get into rehab and nobody’s helping me,” he said. “They got me in a shelter, but I haven’t seen anybody in three weeks to try and get into rehab.”

He said that while there are some resources for those suffering from addiction, there isn’t nearly enough.

“I want to see more rehabs,” he said. “Get us some more help. I want to get some more detox beds. They’re really not doing [anything] for us right now. Especially if you’re an addict. If you’re an addict, they’re looking at you like you’re the scum of the Earth right now. I wish the city would give us more beds, more opportunities. Help us.”